The more astute readers out there will have noticed that there’s been a slight design change around here. I’ve actually just finished migrating from Hugo to WordPress. But why? When I first resurrected this blog, I wrote a post about my reasons for selecting a static site generator (Jekyll then Hugo) in the first place. So what went wrong?

Well to be honest, although the setup was working really well most of the time, there were a few situations where I found it lacking.

Drafts

I was finding the process of writing a draft post a bit “fiddly”. Because every commit to the blog’s Git repository is deployed automatically, I couldn’t commit any unfinished writing without first remembering to set some special flags at the top of the post, in the front matter. Those flags would need to mark the post as a draft, tell the system not to render the page, and not to add it to the posts list and RSS feed. Occasionally I would forget those steps and accidentally “publish” a half-finished mess. It was a bit frustrating.

Image galleries

Dealing with images was also painful. You’d need to deal with naming them, putting them in the right subfolder, and then adding them to the document using a shortcode. I ended up writing some custom code to make creating a gallery of images easier, as I was finding myself making use of the feature quite often, but it was still quite painful to deal with.

Writing on the go

The static site generator approach required me to have a way of writing Markdown and then committing it to a Git repository, then finally pushing the changes up to GitHub. There were plenty of times where I’d be waiting for an appointment, or going somewhere on public transport, where I could’ve done some writing, but this process doesn’t lend itself well to a smartphone environment. It just wasn’t feasible.

I tried to get a workflow going using a really nice Markdown editor called iA Writer, which is a great bit of software, but I was still left with the problem of how to manage the Git side of things. Writing the posts was one thing, but getting them published via my Git workflow just wasn’t a great experience on the go.

Looking at alternatives

If something isn’t working right, try something different. There’s really no need to settle. I decided to look into my options.

I started with some research of various approaches. I wanted something flexible, but not complicated. I wanted something that had a nice editing experience, and good performance. I had also decided that my days of self-hosting were over, so I wanted something that provided a fully hosted version, so I could forget about managing anything, and just focus on writing.

I looked at what some of my friends were using. Things like Medium, or Substack seemed to have a slightly different aim, and I wasn’t sure about some of their policies. Eventually I found myself right back at WordPress. Many years had past since I last used this software, and I was pleasantly surprised to see how it had evolved, so I decided to take it for a whirl.

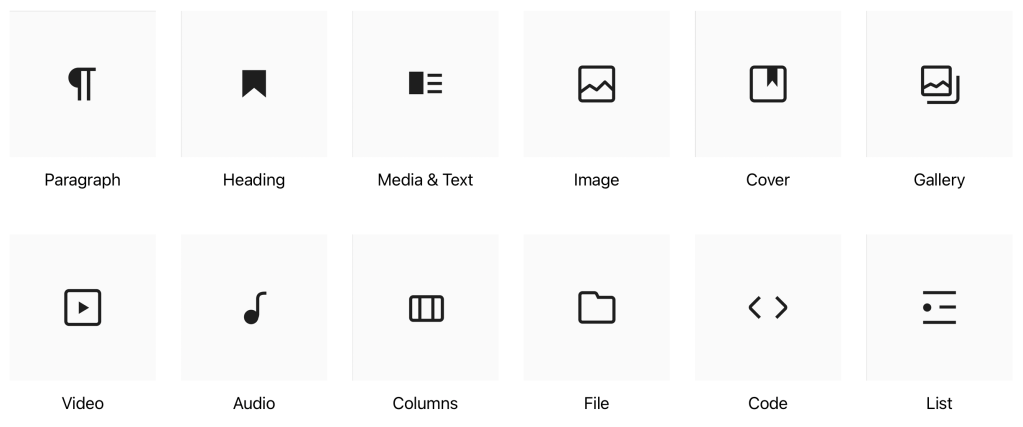

Gutenberg

The star of the latest version of WordPress has to be the new Gutenberg editor. This new way of creating your posts and pages relies on a range of different components called “blocks”, which you can move around the page as required, and it really gives you a huge amount of flexibility. There is an interactive demo of Gutenberg which you can explore for yourself to see what I mean.

Themes that support this type of editor are pretty customisable too, offering predefined areas on the page for you to edit, such as footer, sidebar, and header areas, giving you a remarkable amount of flexibility without needing to do any coding at all. You can also create reusable templates of common blocks to avoid having to edit them in multiple different places.

Initially I did find it a bit daunting, but I stuck at it, trying the various pieces out, and in the end I found that I quite liked it. I decided to bite the bullet and started the process of moving back to WordPress.

Migrating

I decided to migrate my previous posts manually rather than using a tool. This gave me the opportunity to re-work some of the posts I was less happy with, and after all we were only talking about a dozen posts, so I knew it wouldn’t take too long. This also gave me the chance to check the formatting, make sure hyperlinks worked, and to take advantage of the Gallery block to upload the full sized versions of any images I had used.

Migration was straightforward because in most cases I was able to copy and paste from the existing site into Gutenberg, and it correctly interpreted everything, including subheadings, code blocks, and even things like pull quotes; they were all converted correctly into the equivalent block type.

Finally, I decided I didn’t want to have to deal with comments on the posts, so I turned off the entire commenting feature. I figured people can always reach me on Mastodon to discuss things, and having to deal with the inevitable spam here didn’t appeal.

I checked everything looked good, checked the RSS feed was working properly, and hit the button to go live. The rest, as they say, is history.

I’m pretty happy with how it’s turned out, and I’m hoping this will encourage me to post more as well.

Here’s hoping!

.](https://rylon.dev/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/alpine-docker.png?w=900)

](https://rylon.dev/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/cicd-1.png?w=826)

It results in a huge useless diff of likely unrelated changes. Other contributors working on the repository will find it more difficult to read and understand your work. This also applies to yourself once enough time has passed!Consider making small, regular commits as you go, in groups of related changes, rather than everything at the end in one go.

It results in a huge useless diff of likely unrelated changes. Other contributors working on the repository will find it more difficult to read and understand your work. This also applies to yourself once enough time has passed!Consider making small, regular commits as you go, in groups of related changes, rather than everything at the end in one go..](https://rylon.dev/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/railway.png?w=512)